Explanation 1: We started quilting because I was bored in my own classroom, and my kids were too.

Explanation 1: We started quilting because I was bored in my own classroom, and my kids were too.

This particular class is "physical computing," which it's never really been. It's the wrong name for a class that's meant to be an exercise in "Making" and craft and experimentation. We did a bunch of traditional Maker projects earlier in the year - soft circuits, paper circuits, MaKey MaKey - but most of my kids weren't especially into it. So, we started moving into other spaces - knitting, making Mexican wrestling masks, puppets. It was better, but still not as much discomfort as I would have liked. I want my kids to push their thinking on a daily basis in ways that inspire their curiosity. This wasn't happening.

Explanation 2: We started quilting because I don't know how to do it.

So I interrupted everything they were doing - or not doing - about a week ago and announced, after about 24 hours of thinking about this, that we were going to do quilts as our final class project. (We end in December.) Now, prettttty much everything I know about quilting I've learned in the past week. I ordered some books, watched some videos, and figured "I'll use this as an opportunity to model my own learning." I was really inspired by Libs Elliott's Processing Quilts, and had imagined that's what we would base our own work on. But alas:

Explanation 3: I don't know what I'm doing IN A VERY BAD WAY

We're a week in, and I'm feeling now that this may be the worst idea I've ever had since telling my very first class of 7th graders that we were making a music video after planning the entire project during a single 45-minute prep right before the period started. Here are just a few of the problems:

> I did not limit the size of their quilts. I have some students who are insisting on making bed-sized quilts. They have not made quilts before. If I had this to do over again, I would say 12" x 12", and that's it.

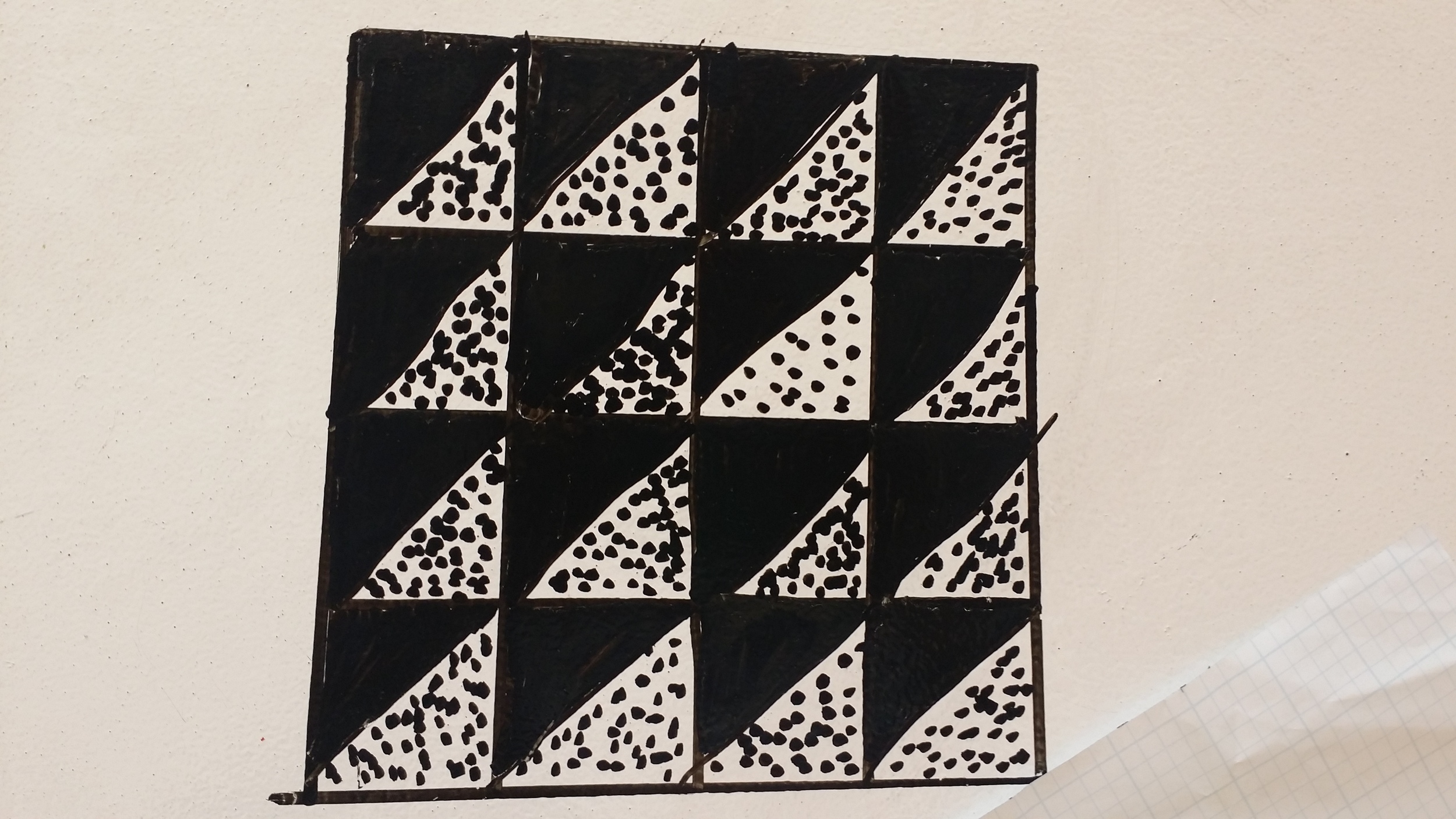

> I did not constrain their designs. I have some students who are very attached to the idea of making, oh, I don't know, something that looks like this. Ohhh dear. Next time it's all squares and triangles, my friends.

> I do not know how to explain how much fabric one requires (in yards off a bolt) if one has, say, 36 3" x 3" squares. I can figure this out by myself, but cannot seem to explain it to anyone. One student did manage to figure it out, probably by doing it herself, and I now rely on her to explain it to everyone else.

> I have no budget.

Current status: Frustrated + Terrified + (some fraction)Inspired.

Photos to come.