I've wanted to teach a physical computing class for the past year or so, but I've been holding off because I feel like I don't know enough to teach it. (I have considerable experience teaching things I don't know much about myself, so this is saying a lot.) ITP Camp forced me to get my act together in June, and I'm going to be teaching one section of "Electronics"* for nine weeks, mid-September to mid-November. So now I have to plan it. With nine weeks and three hours / week, I'm looking at 27 hours of classes. I'm tentatively thinking about:

I've wanted to teach a physical computing class for the past year or so, but I've been holding off because I feel like I don't know enough to teach it. (I have considerable experience teaching things I don't know much about myself, so this is saying a lot.) ITP Camp forced me to get my act together in June, and I'm going to be teaching one section of "Electronics"* for nine weeks, mid-September to mid-November. So now I have to plan it. With nine weeks and three hours / week, I'm looking at 27 hours of classes. I'm tentatively thinking about:

One week of simple circuits (paper pop-ups, basic electricity stuff) to get a sense of who's in the class, let the rosters settle down, and make something fun right away; and

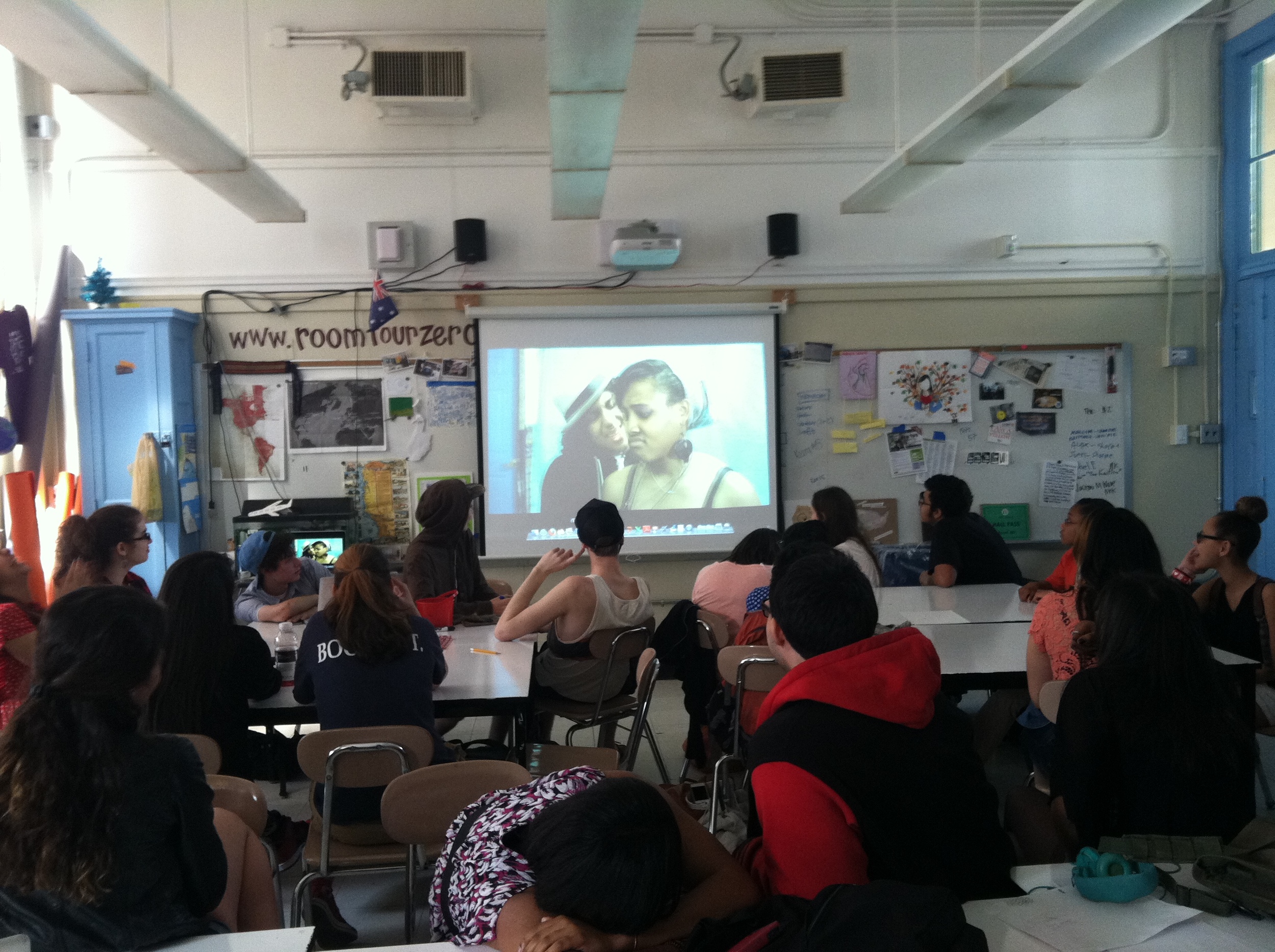

Eight classes each on three different projects (see below) that students will rotate through in groups of <10. The logic here is that we have limited supplies/equipment and potentially 28-30 kids, and if we rotate, I can make sure that the 3D printer (assembled over 25+ hours by Fran Fay and myself, see above, which I'm pretty proud of but I'm still not sure if it works) is pretty much being used all the time, rather than very intensively for a few weeks.

> 3D printing / still not sure how to do this, but will figure it out. I'm imagining that we'll do something simple in Sketchup and everyone will be able to print something simple in (or outside of) 8 hours. Naive / impossible?;

> Wearables / we can begin with soft circuits (sewing, lights) and then move to lilypad. I can get ~10 Lilypad simples that can be reused, and I think we'll have time for simple sketches;

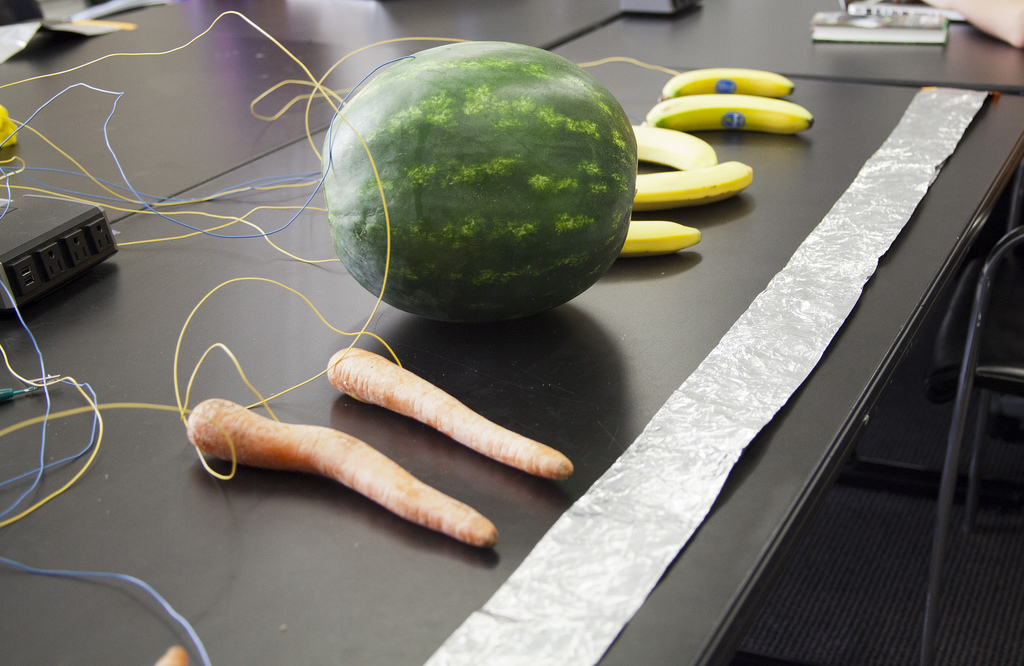

> MaKey MaKey / basically because it's awesome, it's simple but there are so many possibilities, and because our music teacher can use them as well. Can I get away with 4 sets for <10 kids?

Big questions: I can only dedicate one course to maker-y things (I also teach feminism and cartography), which means that I'm making a choice to do ~4 projects in a very simple way rather than 1 activity (eg, wearables) more intensively. Bang/bucks. Is this wise or unwise? I thought this was a good idea until I saw it written out here, and now it sounds crazy. Is it reasonable to think that my kids (most of whom will have elected to take the class; most will be HS juniors/seniors) will be able to take themselves through these projects with limited direction from me, because I lack expertise and because there would be 3 simultaneous groups that need facilitation? (Documentation is the key word, I think. I expect to have some materials to get them started.) What supplies must I acquire that I haven't thought of? Should I throw my hands up and do it in the spring instead?

I'd truly appreciate any thoughts / recommendations / (dis/en)couragement you might have - I need your honesty.

*What should I call the class? Mary Moss suggested iSchool Media Lab (after MIT), which I like a lot but I now fear that it would look too much like "Microsoft Office Suite, High School Edition" to most. Thoughts?